Chester Higgins Jr.: Mastering the Black Gaze in Photography

Introduction

“I don't take pictures. I make them.” — Chester Higgins Jr.

If you’ve ever struggled with how to honour your heritage while building a name in an industry that rarely sees you fully, Chester Higgins Jr. offers something rare: a map. Not the kind found in textbooks or career guides, but one traced in light and shadow, through portraits that carry soul, dignity and ancestral memory.

For Black photographers navigating an often exclusionary industry, Higgins’s journey is not just inspiring. It’s essential. He didn’t simply succeed in a white-dominated field; he reshaped it. Over five decades, his images have documented everyday Black life, global African traditions and the sacred intimacy of community, always from the inside.

His camera is not a mirror. It is a compass. One that points toward liberation, memory and truth.

Through Higgins’s work, we witness the transformative power of the Black gaze, a way of seeing that restores agency, complexity and care to Black subjects often flattened or erased by mainstream media. And at a time when representation remains hotly debated, his lens feels more relevant than ever.

What makes a master of photography?

To call Chester Higgins Jr. a master is not flattery. It’s fact. But what does mastery mean when you are Black in a world that too often refuses to see your genius?

Technical Proficiency

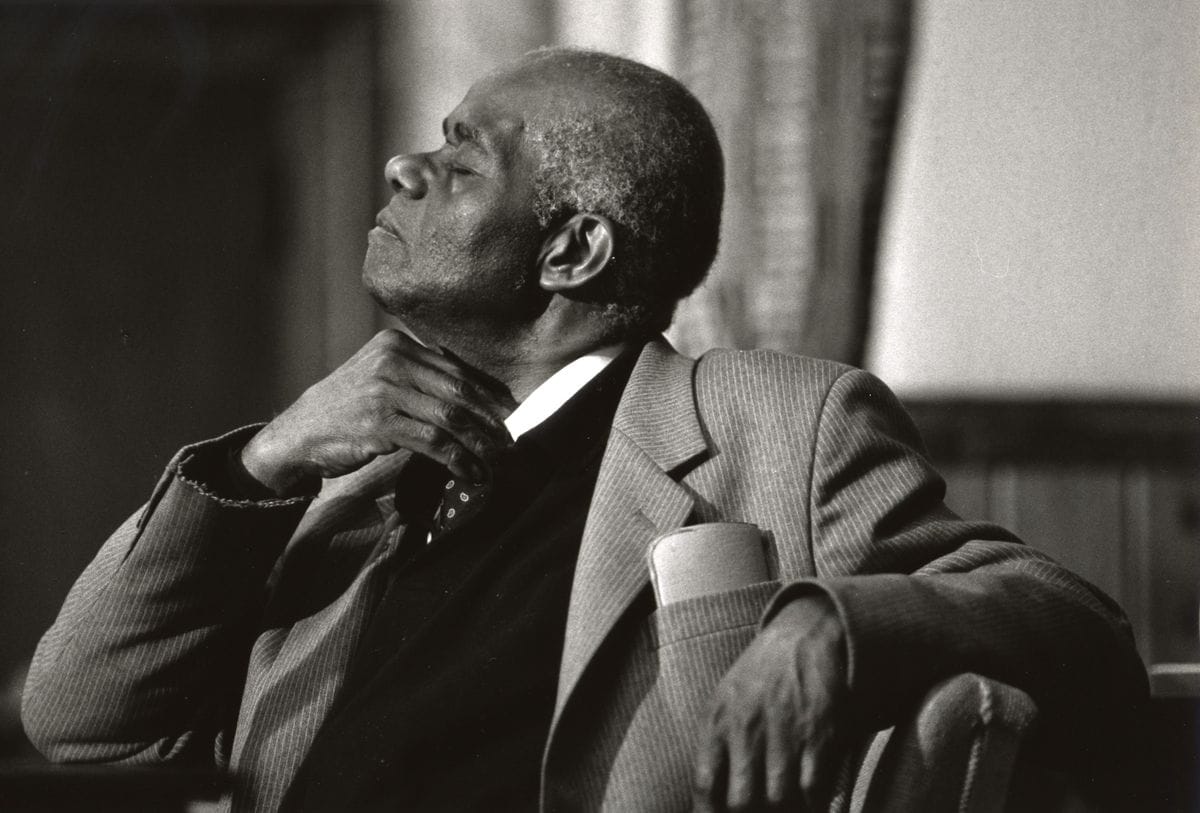

Higgins's command of light, especially natural light, is second to none. His portraits are rich in detail, his tonal range exquisite. Whether in high-contrast black-and-white or lush colour, his compositions are intentional, his subjects anchored in dignity. He once said, “Light is spirit.” He doesn’t just photograph people, he reveals their essence.

Artistic Vision

What sets Higgins apart is the clarity and depth of his perspective. Every image begins not with the eye, but with the soul. His photographs are emotionally resonant because they are spiritually grounded. His recurring focus on family, ritual, intimacy and the African diaspora makes his work more than documentary, it’s devotional.

Innovation & Influence

Higgins didn’t wait for permission to tell stories about his people. He brought them to The New York Times, where he worked for nearly four decades, and into books, exhibitions and archives around the world. His 1994 book Feeling the Spirit: Searching the World for the People of Africa remains a landmark in diasporic visual storytelling. He was among the first to reframe African traditions not as exotic, but as sacred and living.

Cultural & Historical Impact

Higgins’s work challenges erasure. From Harlem to Ethiopia, Alabama to Senegal, his photography bridges ancestral memory with present-day realities. He is part griot, part activist, offering visual counter-narratives to centuries of colonial and racist imagery. In doing so, he has helped shape how generations understand Black identity.

Consistent Excellence & Recognition

Higgins’s career spans over 50 years, with his work exhibited at the International Center of Photography, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Schomburg Center. His archive, continually growing, is a treasure trove of Black cultural history. He has received countless awards, but more importantly, his images live in the hearts and homes of the communities he photographs.

For emerging photographers, Higgins is proof that mastery is not just about technical skill, but about vision, integrity and commitment to truth-telling, especially when the world refuses to look.

Biographical context

Early life & community roots

Born in 1946 in Fairhope, Alabama, Chester Higgins Jr. grew up in the deeply segregated American South. His earliest memories were shaped by a world that tried to limit Black ambition, yet his family and community instilled in him a sense of purpose and pride. Raised in a churchgoing household, Higgins absorbed the importance of ritual, symbolism and community, themes that would later define his photographic voice.

His father was a merchant marine, often away, but his mother and grandfather ensured he grew up with a clear sense of his people’s strength and history. That familial grounding became a wellspring of inspiration. “I was raised in a household that believed in the goodness of Black people,” he once recalled. That belief echoes through every image he has ever made.

Education & early career

Higgins attended Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), where he studied business. But it was there, surrounded by Black intellectual tradition and cultural pride, that he discovered photography, and more importantly, his calling. The turning point came when he encountered the work of P. H. Polk, the university’s official photographer, whose portraits of Black Southern life spoke volumes without words.

Armed with a camera and a sense of mission, Higgins taught himself the technical skills he needed to document the truth of his community. His first major opportunity came when he photographed civil rights leader John Lewis, an image that caught national attention.

Path to photography

While many photographers begin with art school or apprenticeships, Higgins’s path was forged in the fire of necessity. His lens was shaped by the realities of racism, the urgency of representation, and a desire to honour the sacred in Black life. He joined The New York Times in 1975, one of the first Black photographers to work there, and remained on staff for over 38 years.

Yet even at one of the most prestigious newspapers in the world, he never wavered from his mission: to centre Black people, Black joy and Black history in the frame.

Artistic approach & themes

Chester Higgins Jr. is more than a documentarian. He is a visual poet whose camera translates spirit into image.

Mastery of medium

While he has worked in both colour and black-and-white, Higgins is best known for his luminous monochrome images. Black-and-white, for him, is not a constraint. It’s a tool for emotional truth. Without the distraction of colour, the viewer is drawn into gesture, expression, light and shadow, the elements that convey soul.

His recent work, however, leans into colour, especially in his Sacred Nile series. Here, colour becomes a language for divinity, nature and ancestral presence. Higgins proves that mastery lies not in the medium, but in how you use it to tell the truth.

Composition to tell stories

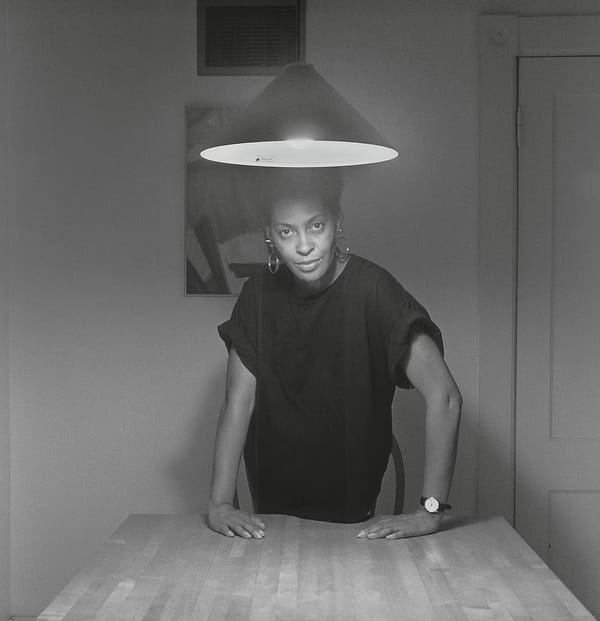

Higgins uses light as both brush and metaphor. He favours natural light, often positioning subjects in front of windows or outdoors to capture softness and dimensionality. His compositions are deceptively simple, placing people in relationship with their environment, whether that’s a Harlem stoop or an Ethiopian temple.

He often frames his subjects centrally, giving them authority within the image. Eyes meet the camera. Postures are upright. Nothing is accidental. Everything is invitation.

“The picture is not just what you see. It’s what you feel.”

For aspiring photographers, Higgins’s work is a masterclass in intentionality: pay attention to light. Let your subjects lead. Honour the truth in their faces.

Use of symbolism and metaphor

One of Higgins’s greatest strengths is his ability to weave symbolism into everyday imagery. A woman holding a Bible becomes a vessel of ancestral resilience. A child’s hands at prayer echo centuries of spiritual endurance. A man in profile, half-lit, suggests both historical burden and future potential.

In Sacred Nile, Higgins uses rivers, temples and statues as metaphors for the enduring spirit of African civilisation. These are not tourist images. They are sacred records. They tell stories of origin, exile and return.

Recurring themes

- Poverty & social injustice: Though never voyeuristic, Higgins doesn’t shy away from hard truths. His early work in Alabama and Harlem documents the material realities of Black life under systemic oppression.

- Racism & civil rights: From photographing Black leaders to street protests, Higgins has chronicled Black America’s ongoing struggle for justice with dignity and clarity.

- Everyday life of African Americans: One of Higgins’s signature contributions is his documentation of Black life beyond trauma; Sunday church services, kitchen conversations, quiet love. These images are radical in their normalcy.

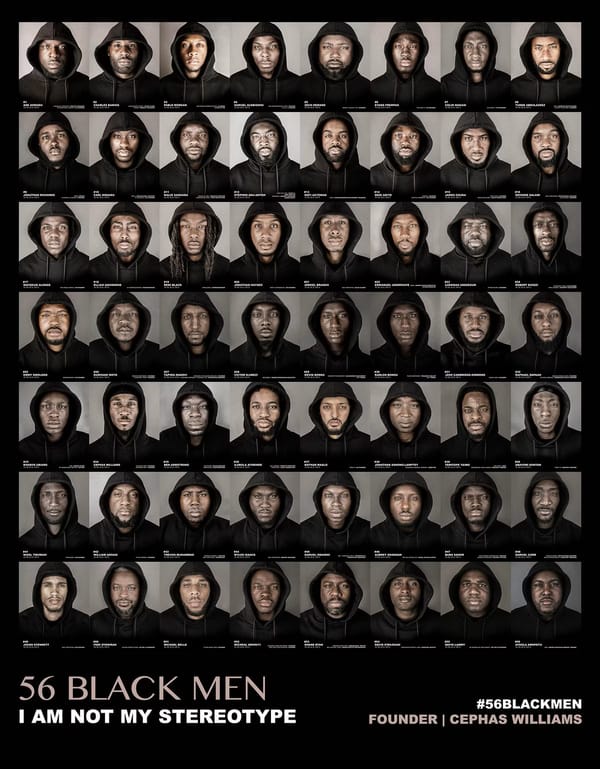

- Empowerment & representation: Higgins’s portraits do not extract. They honour. Every subject is presented with respect and autonomy, countering centuries of dehumanisation.

- Challenging stereotypes through authentic portrayal: Whether in America, Africa or the Caribbean, Higgins resists caricature. His lens insists: we are complex, holy, beautiful and whole.

“Their portfolio captures not just individual stories, but the collective spirit of a community, reminding us that photography can also serve as a tool for communal solidarity and healing.”

The Black gaze

Standing apart from the mainstream gaze

To understand Chester Higgins Jr.’s work is to understand the power of looking from within. The mainstream gaze has long captured Black subjects through a lens of distance often exoticised, pitied, or objectified. Higgins offers an antidote. His is an insider’s perspective, one rooted in shared history, cultural understanding, and mutual respect.

“I use my camera to affirm the nobility of the people I photograph,” he once said.

His images are not looking at Black people. They are looking with them.

In portraits like The Father and Son at Prayer or Women with White Veils, Ghana, Higgins captures gestures of intimacy and spirituality that can only be documented with deep trust and relational care. These aren’t performances for an audience. They’re expressions of life as lived.

Techniques for depth and humanity

Higgins’s compositions are rich with visual storytelling. He often uses close-ups to emphasise facial expressions, hands, or the texture of skin, physical details that carry emotional weight. In other works, he uses wide shots to place his subjects in spiritually or historically loaded landscapes, connecting individuals to collective memory.

In his Ancient Nubia series, the use of shadow, symmetry and colour evokes not just presence but legacy. His work is layered, simultaneously literal and symbolic, personal and historical.

Defying default narratives

In defiance of dominant portrayals that frame Africa as primitive or Black Americans as perpetually struggling, Higgins reclaims imagery. In Feeling the Spirit, he documents Black churches with reverence, not spectacle. In Sacred Nile, he traces African heritage across geography and time, placing African civilisations at the centre of human history, not its margins.

His photography actively resists the visual tropes of poverty porn or cultural voyeurism. There are no passive bodies, no empty stares. Each subject carries dignity and story.

Influence on other photographers

Higgins’s approach has deeply influenced a generation of Black photographers who aim to document from within rather than observe from without. His emphasis on spiritual connection, respect, and cultural fluency continues to shape conversations about the Black gaze today.

For young photographers wondering how to hold cultural truth while innovating creatively, Higgins provides a model: look inward first. Trust the stories only you can tell. Honour the lives around you.

“The lens through which we see the world must reflect not only what is, but what we believe it can be.”

Breakthroughs & mastery

Major career milestones

Chester Higgins Jr.’s professional journey is marked by landmark achievements — but what makes these moments so powerful is how they validate a vision that has always centred Blackness on its own terms.

He joined The New York Times in 1975, becoming one of the paper’s first Black photographers. There, he covered everything from presidential campaigns to community vigils, never diluting his perspective. In a newsroom that often prioritised detachment, Higgins insisted on intimacy and respect.

His books, including Black Woman, Ancient Nubia, and Echo of the Spirit, have become foundational texts in the visual archive of the African diaspora. His photographs have appeared in Time, Ebony, The New Yorker, and exhibitions around the world.

Relating milestones to collective aspiration

These achievements are more than personal wins. For Black photographers navigating underrepresentation, Higgins’s rise offers proof that it’s possible to break into elite institutions without compromising your vision.

He didn’t simply make it to the top. He changed what the top looked like.

If you’ve ever dreamed of your work in MoMA or the Smithsonian, or of creating a photo book that lives in homes across generations, know that Higgins once dreamed too. His life is a reminder that mastery doesn’t require permission. It requires persistence, belief, and clarity of purpose.

Notable projects & community impact

Among Higgins’s most important bodies of work is Feeling the Spirit: Searching the World for the People of Africa, a photographic journey across the U.S., Africa, the Caribbean and Brazil. The project charts how African spiritual traditions — Christianity, Islam, Vodou — persist and adapt across time and place.

It’s not a story about the diaspora as scattered. It’s about the diaspora as connected through ritual, rhythm and resilience.

He’s also worked closely with Black churches and grassroots organisations, often returning to the same communities year after year. These aren’t one-off photo ops. They’re relationships.

“By working directly with local groups, Higgins created images that came from within the community rather than an external viewpoint.”

Work across mediums

While photography remains his core medium, Higgins has also used writing, curating and public speaking to amplify his message. His books integrate essays and personal reflections. His exhibitions often feature soundscapes, historical timelines, or cultural artefacts to deepen audience understanding.

This multidisciplinary approach reflects his belief that photography is not just a visual art, but a narrative force, one that can heal, connect and awaken.

Impact on the art & audience

Influence on photography

Chester Higgins Jr. has changed how we understand what photography can do and who it can serve. His presence in major institutions like The New York Times, MoMA and the International Center of Photography broke through barriers that long excluded Black voices. But more importantly, his work carved space for others to follow.

He didn’t just open doors. He redesigned the architecture.

His legacy is especially evident in the work of contemporary photographers like Devin Allen, Adama Delphine Fawundu, and Andre D. Wagner, artists who document Black life with nuance, beauty and a deep sense of place. Higgins proved that you could be both documentarian and storyteller, technician and theologian.

His work demonstrated that photography is not neutral. It is political. It is spiritual. And it is most powerful when it emerges from the lives of those who have something urgent to say.

Cultural & social impact

Higgins’s photography sits at the intersection of art and activism. Whether capturing Harlem churches or Ethiopian ceremonies, his images challenge the narrow definitions of Blackness often found in media and education.

He expanded the visual vocabulary of Black life, one that includes joy, faith, resilience and community, alongside struggle. In doing so, he offered new ways of seeing, not only for white audiences unfamiliar with the richness of Black culture, but for Black viewers long starved of affirming imagery.

His portraits insist: you are sacred, seen and whole.

Recognition & legacy

Higgins’s accolades are extensive. His photographs are held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Schomburg Center, and the Library of Congress. He has received awards from the International Photography Hall of Fame and was named a Living Legend by the National Black Arts Festival.

But perhaps his greatest legacy is the body of work itself, vast, varied, and deeply intimate.

His archive is more than history. It’s inheritance.

Q. How will you contribute to a new canon that centres truth, honour and community?

What role do you see your own lens playing in the ongoing fight for racial equity and narrative control?

How will you contribute to a new canon that centres truth, honour and community?

Reflections on the Black gaze

Challenging the default gaze

Chester Higgins Jr. never asked permission to see his people clearly. He challenged the Eurocentric gaze that has long shaped how Black people are photographed — as danger, as curiosity, as spectacle — and instead offered a vision grounded in care.

Where others might search for poverty or pain, Higgins found ceremony, reverence and strength. His lens deliberately avoids the sensational in favour of the sacred. He centres joy without ignoring struggle. And he shows that to see Blackness fully, you must first be willing to love it.

His work dismantles the myth of objectivity. He replaces it with relational seeing, a gaze informed by shared history, cultural knowledge and emotional depth.

Subverting narratives

One of Higgins’s most subversive acts is his refusal to other his subjects. In Echo of the Spirit, for example, he reframes African religions not as superstition, but as sacred knowledge. In his portraits of Black American elders, he highlights wisdom and grace rather than decline.

He shows what happens when we tell our own stories: the frame expands. The narrative deepens. The truth becomes less about suffering and more about survival, beauty and legacy.

Cultural symbolism & community building

Higgins’s imagery is full of cultural markers — white headwraps, open Bibles, incense smoke, braided hair — that carry generations of meaning. These symbols are never decorative. They are declarations. They say: we were here, we are here, and we are not going anywhere.

He creates community through photography, not by documenting people from the outside, but by standing among them. His camera isn’t extractive. It’s invitational.

How can you apply his principles of the Black gaze in your own creative endeavours?

Continued relevance

Today, as conversations around racial equity, media bias and artistic gatekeeping continue to evolve, Higgins’s work remains deeply relevant. He provides a blueprint for how photographers can both honour their heritage and speak to the present.

He reminds us that the Black gaze is not reactionary. It is not simply resistance. It is creation, a proactive shaping of meaning, culture and future.

Closing thoughts & takeaways

Summary

Chester Higgins Jr. is not just a master of photography, he is a master of meaning. Through light, composition and cultural care, he has elevated the Black gaze from an overlooked perspective to a powerful, guiding vision.

His technical skill is exceptional, yes. But it’s the soul of his work that truly defines him. From the pews of Harlem to the temples of Nubia, Higgins has photographed Black life with intimacy, depth and reverence. His artistry is as much about truth-telling as it is about honouring.

He has shown that mastery in photography is not simply about capturing the moment. It is about capturing memory. Culture. Legacy. Dignity.

For Black photographers navigating questions of voice, representation and visibility, Higgins offers a profound reminder: you do not need to mimic the mainstream to matter. Your story, your people, your gaze are enough.

Final reflection

Photography is not just about aesthetics. It’s about authorship. It’s about power. And in a world that still too often distorts or deletes Black stories, your camera can be a tool of reclamation.

Let Higgins’s legacy embolden you. Tell your truth. Honour your people. Create work that sees, remembers and uplifts.

Call to action

Whether you are just beginning your photography journey or seeking to deepen your creative voice, here are some next steps:

- Watch Chester Higgins Jr. talk about The Camera Means Nothing Without Your Vision on The Black Shutter Podcast.

- View more of Chester Higgins’s work through his official website, books (Feeling the Spirit, Echo of the Spirit, Sacred Nile) and recent exhibitions.

- Engage with Black photography collectives such as Black Women Photographers, The Authority Collective or See In Black for community, mentorship and collaboration.

- Join online challenges or forums that centre Black perspectives in visual storytelling.

- Attend local exhibitions and talks that explore themes of identity, memory and social justice through photography.

- Reflect on your own gaze. What stories are you telling and whose voice is leading the frame?

Photography is more than documentation. It is direction. Let Chester Higgins Jr. remind you to look inward first, and then out. Not with fear, but with purpose.

Share on social

If this story sparked something in you, share it. Our voices are powerful, and when we lift each other up, we all see a little clearer.

Contribute

At theBLKGZE, we don’t just reflect the world, we reshape it. We’re building an archive that centres Black vision and truth. We reclaim the frame. We archive what’s been silenced. We honour the everyday and the extraordinary in Black life.

We’re calling on Black photographers to contribute. Add your voice to the archive. Let's reshape the narrative with a truer picture of who we are and who we’ve always been.