Wi likkle but wi tallawah

How the de facto gaze distorts photography rooted in Jamaican culture, and how the Black gaze reclaims it

“Representation is a theatrical one … the Orient is the stage on which the whole East is confined.” - Edward Said

Edward Said’s observation still resonates. Photography has long served as an instrument of empire, used to define, diminish and control. Today, misrepresentation of Black life remains widespread in Western media and institutions. Communities are frequently reduced to spectacles of danger or exoticism, rarely seen in their full humanity.

This essay begins with the persistence of that crisis frame. It maps the scholarly responses that challenge it, then focuses on three photobooks: Boogie’s A Wah Do Dem, Lúa Ribeira’s Noises in the Blood, and Andrew Jackson’s From a Small Island.

Drawing on Tina Campt’s theories of listening and refusal, and Mark Sealy’s call for institutional accountability and visual justice, it asks: What happens when the camera fails to listen? And what becomes possible when it does?

Reframing the gaze: listening, feeling, refusing

Photography is not simply about what we see. It is about how images move us, how they ask us to pause, to dwell, to feel. As Tina Campt insists, the Black gaze is a way of engaging images through vibration rather than vision alone. It is a practice of listening to what the image holds, hides or withholds. It is an invitation to sit with discomfort, to recognise the labour of being seen on one's own terms.

When we view images through this lens, we do not ask, "Does this show the right thing?" Instead, we ask, "What does this image ask of us? What kind of relationship does it make possible? What sounds, silences or sensations are embedded within it?"

Part one: Boogie’s crisis image in A Wah Do Dem

Boogie’s 2019 photobook captures Kingston through flash-lit fragments: masked figures, weapons, dimly lit streets. The work is intense and immediate. Yet it refuses relation. There is no invitation to dwell, only to react.

Listening to these images, we hear what is missing. There is no street chatter, no gospel basslines, no market rhythms. The silence is not peaceful. It is strategic. It turns life into spectacle.

The viewer is kept at a distance. No subject meets the lens. The camera extracts but does not converse. This is not co-witnessing. It is surveillance disguised as street photography.

This image from A Wah Do Dem omits cultural traces. No dancehall flyers, no posters, no everyday ephemera. The archive is emptied of meaning.

And yet, the viewer must ask: what does this refusal generate? Is the absence accidental, or does it reflect a gaze trained on crisis rather than community? What might the same city sound like if documented by those who live within it?

Part two: Ribeira’s visual muting in Noises in the Blood

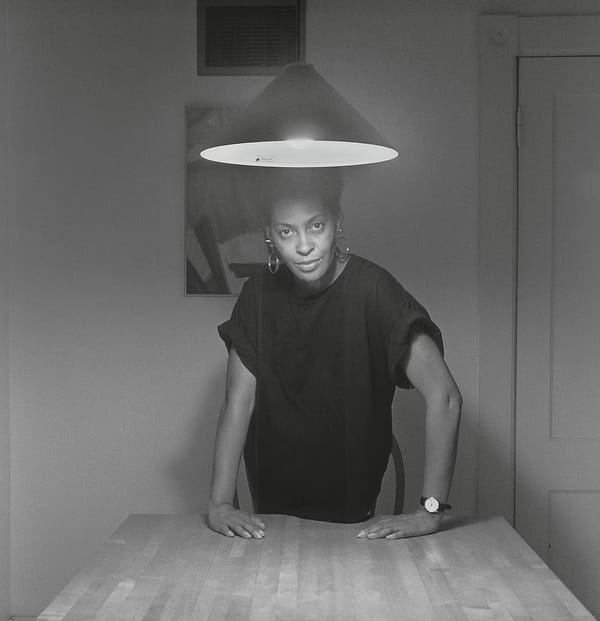

Ribeira’s 2021 book features British-Jamaican women in still poses that allude to dancehall gestures. The spaces are domestic, the styling deliberate, the images beautiful. But they are quiet. Too quiet.

Dancehall is a sonic archive. It lives in basslines, call-and-response, volume. To mute it is to misrepresent it.

The women pose, but they do not speak. Their expressions are self-possessed, yet their stories are withheld. The gaze belongs to the viewer, not the subject. The silence becomes aesthetic.

Without embedded voices, community materials, or sonic residue, the archive feels severed. The image floats, unanchored in diasporic time.

Rather than suggesting refusal, this feels like withholding without critique. Silence here does not generate tension, it generates loss.

Part three: Jackson’s archive of relation in From a Small Island

Andrew Jackson’s 2023 photobook stands apart. It listens. It lingers. It invites.

From A Small Island is an insightful tribute to the Windrush Generation and the hundreds of Jamaicans who following the war travelled to help rebuild Great Britain in the mid-twentieth century.

This photograph of an older Jamaican man captured mid-gesture, standing within a layered urban landscape. His face is tilted upward, his mouth slightly parted, his left hand raised. Not in protest, not in command, but in what feels like memory. The moment is thick with something unspoken.

This is not just portraiture. It is vibration.

This photograph does not demand narrative clarity. It demands patience. The man's gesture interrupts time. He is both here and somewhere else. The vest and loose t-shirt layered over his shoulders feel like a metaphor: histories carried, voices echoed, memory doubled. Neither is fully worn. Both are fully present.

The sounds we imagine are important. Perhaps the voices of children playing in the street. Perhaps the sounds of Irie FM or a local sound system. Perhaps the calling of a street vendor. Perhaps the rustling of trees. The wooden fencing and crumbling zinc roofs are not silent. The fabric speaks. We are invited to hear not what is obvious, but what is residual.

Unlike Boogie's distant gaze, this image feels close. The photographer has not intruded; he has arrived. The man's expression is not for show. It is for someone listening. The viewer is implicated not to decode, but to witness. This is an exchange. It is a gesture that returns.

The photograph does not rely on props. The textures are the archive. The clothes, the skin, the plant growing against rusted metal. Everything here is part of an unwritten but deeply felt record. These are not nostalgic signals; they are living artefacts.

What is refused in this image is performance. The man is not asked to smile, to stage, to entertain. He is allowed to pause, to inhabit his body and his memories fully. This is what Campt calls "the quiet work of refusal." A refusal to be flattened. A refusal to be legible in the terms of crisis or spectacle.

This image reminds us that the Black gaze is not always loud. Sometimes it is contemplative. Sometimes it is still. It is relational, durational and embodied. It does not just document; it resonates.

Dwell, don’t decode

To engage the Black gaze is to abandon the demand for explanation. It is to sit in the vibrational space of the image and ask, "What might this mean beyond what I see?"

Boogie gives us urgency, but no breath. Ribeira gives us posture, but no voice. Jackson gives us time, texture and relation.

This blog post, too, resists resolution. It does not tell you what to see. It asks you to feel. To listen. To sit longer with the image and ask not only, "What is this?" but also, "What is it doing to me?"

That is the work of the Black gaze. Not representation. Resonance.

Share on social

If this sparked something in you, share it. Our voices are powerful, and when we lift each other up, we all see a little clearer.

Contribute

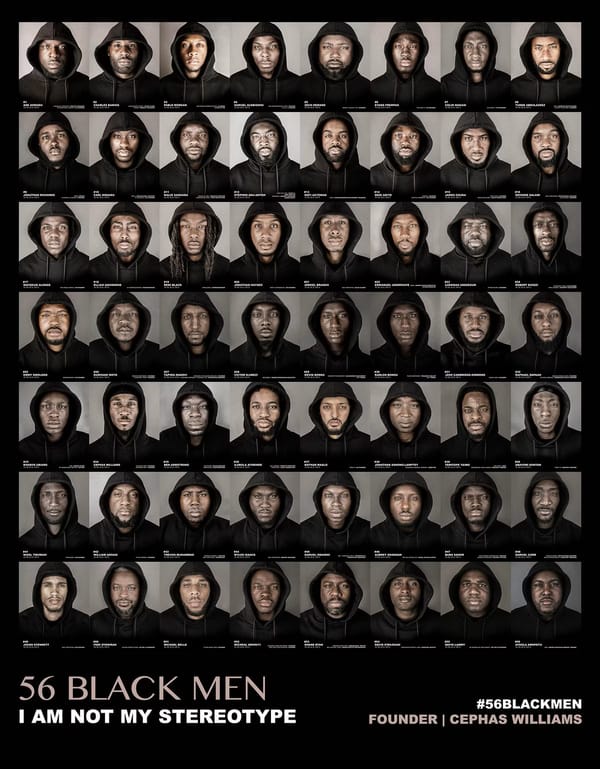

At theBLKGZE, we don’t just reflect the world, we reshape it. We’re building an archive that centres Black vision and truth. We reclaim the frame. We archive what’s been silenced. We honour the everyday and the extraordinary in Black life.

We’re calling on Black photographers to contribute. Add your voice to the archive. Let's reshape the narrative with a truer picture of who we are and who we’ve always been.