The Black gaze vs the de facto gaze

The dominance of the de facto (Orientalist-rooted) gaze

"Representation itself is the main instrument of empire. The power to narrate, or to block other narratives from forming and emerging, is a very powerful tool of control." — Edward Said, Orientalism

What is the de facto gaze?

In photography, the prevailing standard, the "de facto gaze", has long been influenced by Orientalist perspectives. Rooted deeply in historical power dynamics, this gaze often values technical perfection over meaningful representation, frequently resulting in superficial or distorted portrayals of Black life and culture.

How this gaze shapes the image

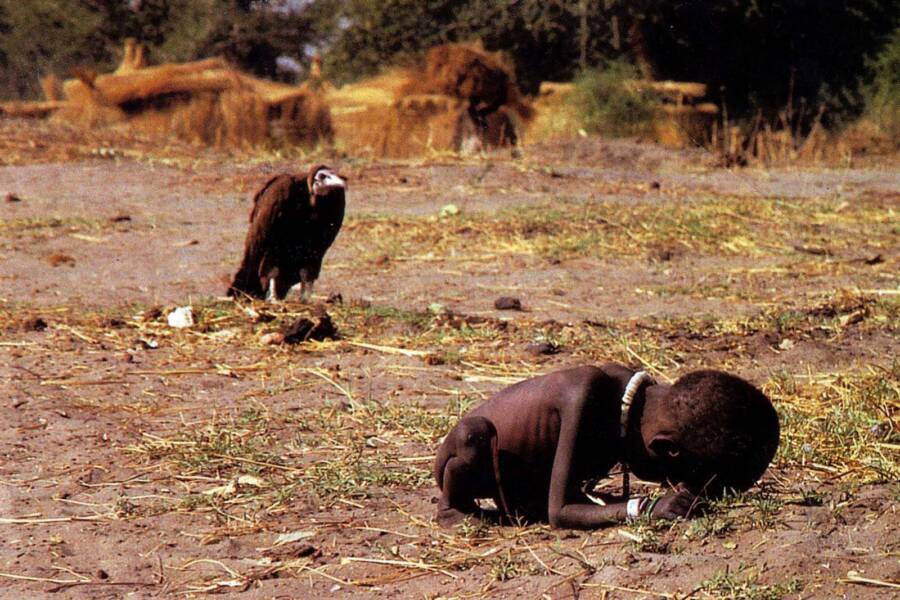

Historically problematic images such as those depicting poverty and violence in African nations by Western photographers have perpetuated harmful stereotypes, presenting Black subjects primarily as aliens, victims or subjects of pity. Photographs like Kevin Carter's Pulitzer Prize-winning image of a starving Sudanese child and Steve McCurry’s portraits, while technically proficient, often reinforce narratives of helplessness or exoticism, rather than agency or dignity.

How it’s passed down through education

Moreover, the de facto gaze is embedded in photographic education and practice, passed down across generations. Many photographers, regardless of race, have been taught to see through a lens shaped by colonialism, Orientalism, and white supremacy.

This institutional inheritance teaches students how to compose technically strong images, but often fails to equip them with the critical tools needed to question what those images imply or perpetuate.

For Black photographers, the impact is especially profound. They may be trained to document their own communities using visual frameworks that were never built to honour or empower them.

As a result, emerging Black photographers can find themselves replicating the very tropes and hierarchies they seek to resist, unintentionally reinforcing narratives that flatten or distort Black life instead of affirming its full complexity.

The impact of misrepresentation and cultural distortion

"We have to stop pretending that photography is objective. Who is behind the camera matters. Who edits, who publishes, and who profits—these things shape the meaning of the image as much as the image itself." — Teju Cole

A long history of misuse

When photography prioritises technical skill over authenticity, it creates images devoid of genuine understanding, empathy, and respect. This disconnect is especially significant for Black communities, where representation has historically been weaponised to diminish self-worth and authenticity

The de facto gaze reinforces biases, distorts Black identities, and sustains a visual culture that fails to resonate with or empower Black audiences.

Photography has long been used as a tool to justify inequality. From pseudo-scientific racial classification to colonial documentation, it has often served to misrepresent and dehumanise Black people.

Colonial-era anthropometric photography, for instance, claimed to provide scientific evidence of racial hierarchy, objectifying individuals and stripping them of their humanity. These images were circulated widely to uphold oppressive ideologies and policies.

Photojournalism and its legacy

In the realm of photojournalism, particularly throughout the 20th century, agencies like Magnum Photos set industry standards yet frequently perpetuated troubling narratives.

Photographers such as Cristina de Middel, Jonas Bendiksen, and Martin Parr, celebrated for their technical skill and aesthetic vision, produced work that at times reinforced problematic stereotypes or exploitative perspectives.

Magnum's influential visual legacy significantly contributed to a culture that frequently overlooked or diminished the depth, complexity, and humanity of Black communities.

Contemporary parallels

Contemporary documentary projects continue to grapple with similar issues. Examples include Pieter Hugo's "The Hyena and Other Men," which has been criticised for exoticising African subjects, and Jimmy Nelson’s "Before They Pass Away," which, despite technical prowess, has drawn significant criticism for romanticising and commodifying indigenous communities. These projects, while visually impactful, often perpetuate problematic, reductive narratives that undermine the dignity and agency of their subjects.

This flawed representation affects how Black people perceive themselves, limits opportunities for authentic self-expression, and perpetuates systemic marginalisation. It deepens misunderstandings, contributing to cultural erasure and reducing vibrant communities to simplistic narratives. By failing to challenge this history, contemporary photographic practices can inadvertently continue to uphold damaging narratives.

Embracing the Black gaze: authenticity, self-worth, and excellence

"To photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude. We must ask: what am I leaving out, and why? Who benefits from this omission?" — LaToya Ruby Frazier

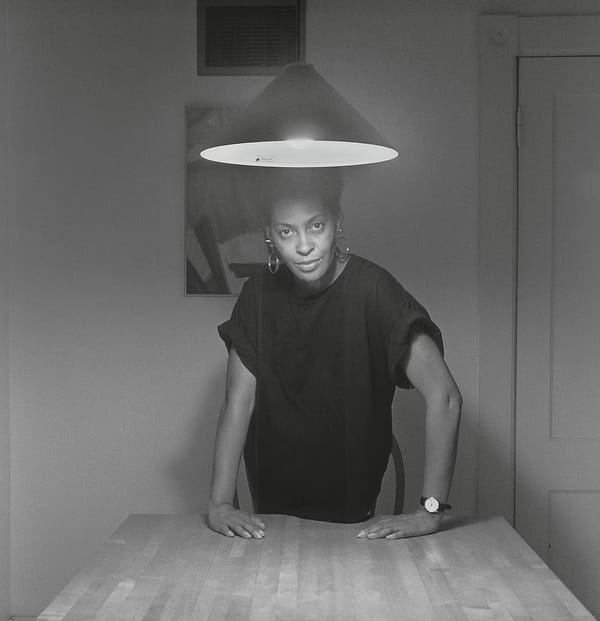

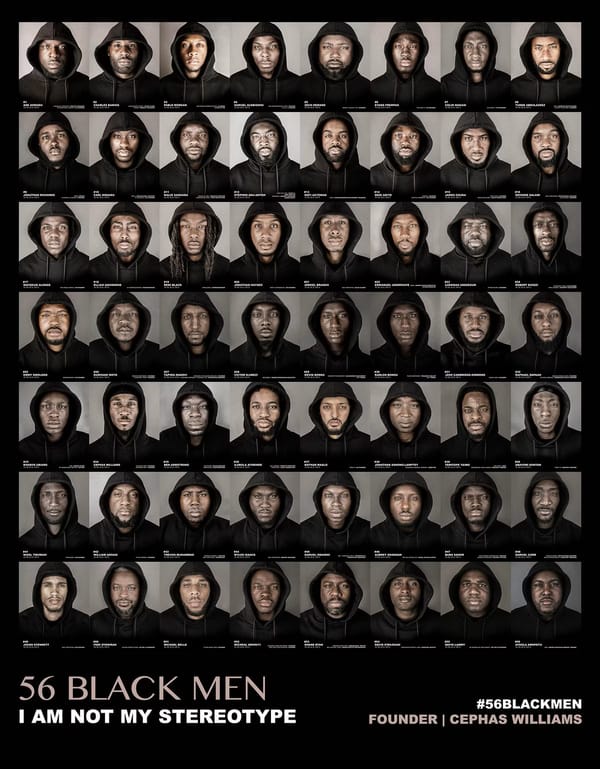

The Black gaze emerges as a transformative alternative, built upon three critical pillars: authenticity, self-worth, and excellence. Unlike the de facto gaze, the Black gaze centres genuine representation, creating images that resonate deeply with the realities and complexities of Black life.

Simply photographing with empathy and professionalism, often considered sufficient by many white photographers, falls short. While empathy and professionalism are valuable qualities, alone they cannot dismantle ingrained power dynamics or historical biases.

These approaches might unintentionally exclude essential context, authentic representation, and a genuine understanding of cultural nuances. They risk creating images that, despite their technical proficiency and superficial empathy, remain incomplete or misleading because they lack deeper cultural resonance and fail to challenge the viewer’s preconceptions.

How photographers can adopt the Black gaze

Photographers aiming to shift away from the limiting de facto gaze towards authenticity can:

- Engage deeply with communities, investing time to build relationships and trust beyond transactional interactions. This involves listening actively, participating genuinely, and understanding the unique dynamics and experiences within those communities.

- Understand historical and cultural contexts, committing to thorough research to appreciate how historical events, systemic structures, and cultural narratives have shaped the lives and perceptions of the people photographed. Such understanding informs respectful, meaningful representation.

- Prioritise empathy and dignity in visual storytelling, ensuring images are captured and presented with sensitivity and respect. This involves considering how subjects might view themselves in the resulting work and avoiding exploitative or sensationalist portrayals.

- Reflect critically on their own positionality, biases, and assumptions, consistently questioning their intentions, privileges, and perspectives. Acknowledging one's own viewpoint allows photographers to avoid imposing external narratives and instead supports authentic storytelling rooted in genuine connection.

Through these actions, photographers not only produce technically excellent work but also meaningful, empowering imagery.

Questions we answer time and time again

These are the kinds of questions we hear most often. We share them here to help open dialogue, not shut it down, to help honest photographers move from intention to transformation.

These questions reflect real conversations we’ve had with photographers navigating the complexities of representation. We offer these reflections as a bridge, not to shame, but to deepen understanding and encourage change.

So are you saying that I shouldn’t photograph Black people?

No, we’re not saying that at all. The point is not about whether you photograph Black people, but how you do it, and why. Photography can either uphold systems of inequality or challenge them.

What matters is the gaze you bring, the context you understand, the consent you seek, and the collaboration you foster. The call is not for silence, but for responsibility. If you're committed to telling someone else's story, the least you can do is learn how that story has been told before, and who it’s often left out.

Your care matters, and it's a strong start. But photography isn't neutral, it's shaped by histories of power and bias. When we rely only on our empathy or technical skill, we risk overlooking what we’ve inherited: a visual culture built on distortion, omission, and imbalance.

Doing better means going deeper. It means asking not just how we shoot, but why, who for, and with whose voice. Empathy and professionalism are important, but they are not enough. These traits do not automatically address the deeper issues of historical misrepresentation, power imbalance, and cultural disconnection.

Without a critical understanding of context, your images may unintentionally echo harmful tropes or overlook the agency and complexity of your subjects. True authenticity requires humility, education, and a willingness to challenge inherited visual languages.

I treat everyone the same. Why is that approach problematic?

Equality in approach doesn’t account for inequality in history. A "universal" method often defaults to dominant white visual norms, which can erase the distinct cultural, political, and emotional realities of Black communities. Black representation requires specificity. Without it, your work may flatten what it seeks to honour.

A "universal" approach often defaults to dominant norms, which are rooted in Eurocentric ideals and visual traditions. Black communities have been historically misrepresented, so treating all subjects the same can erase the unique context and significance of their experiences. Photography must account for history, not ignore it.

I'm not Black, can I represent the Black gaze authentically?

The Black gaze is rooted in lived experience and cultural memory, it can't be replicated without that context. But you can learn from it. Instead of attempting to own that perspective, support it. Collaborate, amplify, and question who is behind and in front of the lens. That’s how you begin to shift power, not just aesthetics.

No, the Black gaze comes from lived experience, it is rooted in how Black people see themselves and their communities. However, you can support it by stepping back, platforming Black voices, and being intentional about who tells which stories. Your role might be to document with awareness, or to make space for others to lead.

I follow all the ethical rules. Why is my work still criticised?

Ethics aren’t a shield. They’re a starting point. You might be checking all the boxes, but if you haven’t reflected on your gaze, your position, and your privilege, your work may still uphold the very systems you aim to resist. Criticism doesn’t mean failure, it’s an invitation to grow beyond the rules and toward a more just practice. Ethics are a starting point, not a finish line.

Many photographers unknowingly reproduce problematic narratives even when they believe they are being careful. Critique is part of growth. Instead of defensiveness, welcome it as an opportunity to improve and unlearn.

What's one step I can take today to move beyond the de facto gaze?

Start by unlearning. Audit your influences. Ask: Who do I admire? Who shapes my taste and vision? Then, seek out Black photographers, theorists, and curators. Read their work. Study their practice. Let it challenge and expand your own. This is how transformation begins through curiosity, discomfort, and change.

Start by examining the visual influences you’ve internalised. Whose work do you study? Whose voices shape your understanding of Black communities? Curate your references. Seek out Black photographers, writers, curators, and thinkers who expand your perspective beyond the dominant gaze.

Start unlearning the de facto gaze

Think of this as changing the rendering engine of your photography, not just switching lenses, but upgrading the software that shapes how you see. Just like editing tools allow us to reprocess an image with greater clarity or nuance, unlearning the de facto gaze gives us new tools for seeing with intention, empathy, and depth.

These questions aren't meant to limit your creativity, but to sharpen your vision. They help ensure the image you make reflects not just what you saw, but how you chose to see.

- Who shaped the way I see this subject?

- What history am I stepping into and what assumptions might I be carrying?

- Who is this image really for?

- What story does it tell and who gets to tell it?

- Does this image honour the dignity, agency, and voice of the person in it?

- If someone from this community saw this image, would they feel respected or reduced?

These are not just technical questions, they're ethical and relational ones. The goal isn't to stop creating, but to start seeing differently.

Conclusion

Photography is far more than technical skill, it’s a profound cultural tool with the power to shape public imagination and personal identity. As this piece has shown, technical mastery without cultural awareness can reproduce the very harms many photographers seek to avoid.

Challenging the de facto gaze is not an attack on photography’s traditions, it’s an invitation to expand them. By embracing the Black gaze, photographers can begin to tell stories that resonate with truth, complexity, and dignity.

If you're reading this and feeling unsure, start with curiosity. Reflect on the gaze you’ve inherited. Ask better questions about your intent, your audience, and your influences. Then share what you learn. Challenge your peers. Talk about what needs to change in the photography world, and who gets to define what is excellent.

This is not just a call to change your practice. It’s a call to change the culture around practice. And it starts with you.

Share on social

If this story sparked something in you, share it. Our voices are powerful, and when we lift each other up, we all see a little clearer.

Contribute

At theBLKGZE, we don’t just reflect the world, we reshape it. We’re building an archive that centres Black vision and truth. We reclaim the frame. We archive what’s been silenced. We honour the everyday and the extraordinary in Black life.

We’re calling on Black photographers to contribute. Add your voice to the archive. Let's reshape the narrative with a truer picture of who we are and who we’ve always been.