Blackness doesn’t need to be defined by only struggle

Why has Blackness so often been defined by struggle?

Because struggle is what the camera has most often captured. From the earliest days of photography, Black life has been documented in relation to pain, resistance, and survival. That tradition continues. Press photos of protest, viral clips of violence, campaigns that spotlight injustice.

But this isn’t the only lens we have. It’s just the one that’s been most incentivised.

Why is that the dominant visual narrative?

Because struggle makes a compelling story, especially when told from the outside looking in. Pain feels urgent. It draws clicks. It wins awards.

For too long, Black photographers were excluded from authorship, and so struggle became the shorthand used to speak about us, not with us.

Contemporary artists are shifting this.

Tyler Mitchell creates sunlit, dreamlike portraits that centre Black youth in states of leisure and ease. He was the first Black photographer to shoot a Vogue cover, featuring Beyoncé in 2018. His work expands the possibilities of Black representation by rejecting trauma as the default visual entry point.

Nadine Ijewere is a British-Nigerian fashion photographer whose work celebrates cultural heritage and diversity. She became the first woman of colour to shoot a global Vogue cover. Her portraits challenge Eurocentric beauty norms with softness, colour and individuality.

They remind us that Blackness can be aspirational, stylised, tender, without losing its depth.

Why has this narrowed our understanding of Black identity?

Because repetition becomes definition. If Blackness is always framed through hardship, audiences come to expect it. Worse, some photographers may feel pressure to conform, to document only what fits the pain-first narrative.

Micaiah Carter blends archival aesthetics with modern portraiture to explore Black identity, masculinity and memory. His work draws heavily from 1970s family photos and contemporary fashion. Through stylised imagery, he honours heritage without being trapped by the past.

Ruth Ossai studio portraits of Nigerian youth are bold, colourful and unapologetically local. She uses traditional fabrics, backdrops and styling to elevate cultural pride. Her work flips the script on how African identity is framed, spotlighting joy and performance over pity.

Their lenses don’t flatten. They expand.

Why do photographers need to challenge this framing?

Because photography isn’t neutral. Every frame is a value choice. To centre Black life fully, we must include joy, boredom, creativity, kinship, not just protest and pain.

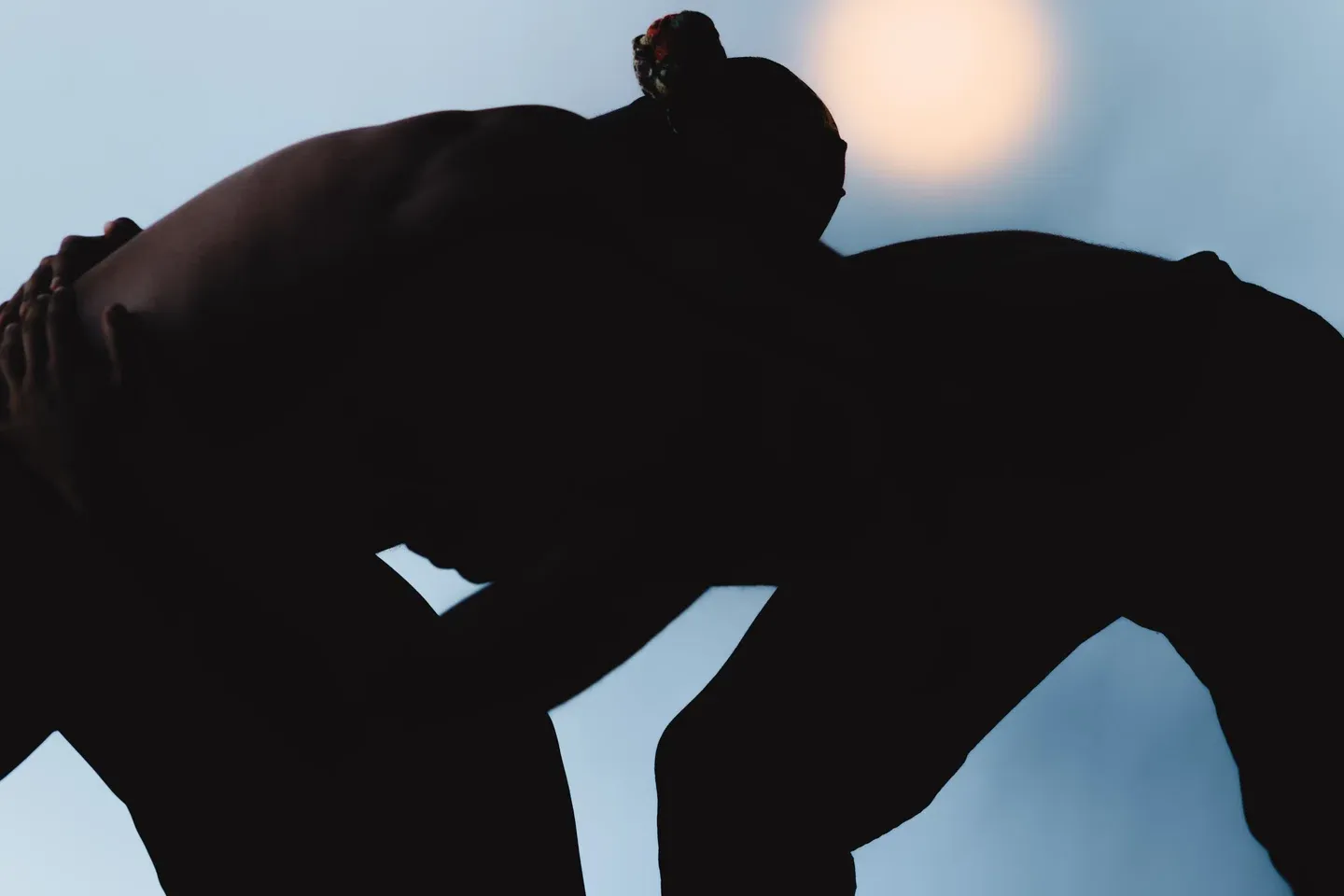

Dana Scruggs is known for her sculptural portraits that reclaim the representation of Black bodies. She made history shooting for ESPN and Rolling Stone as a Black woman photographer. Her images combine strength and vulnerability, challenging one-dimensional views of Black masculinity.

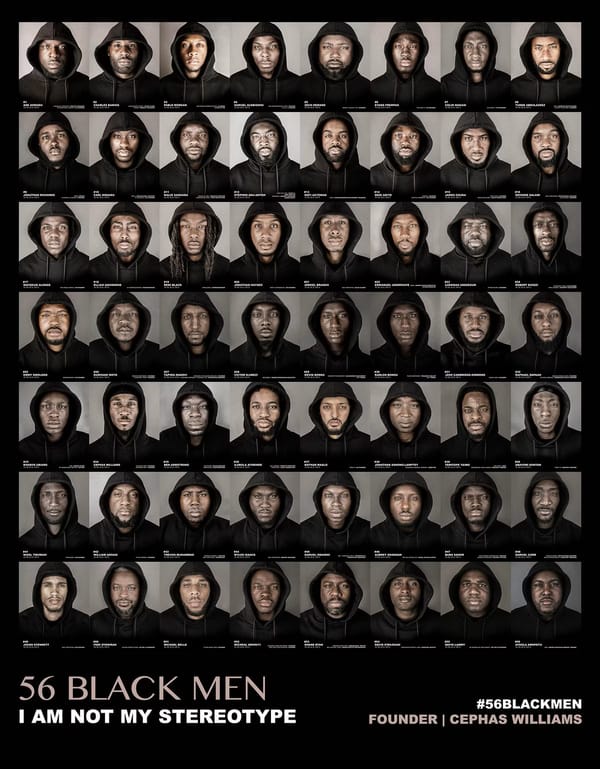

Myles Loftin creates playful, high-energy portraits that centre queer Black joy and visibility. His work breaks down harmful stereotypes through colour, camp and confidence. Projects like HOODED reimagine what Black masculinity can look and feel like.

This isn’t erasure of struggle. It’s balance.

Why does this matter now?

Because visibility is increasing, but representation isn’t the same as liberation. Black photographers are gaining platforms once denied. But with access comes risk: to be boxed in, tokenised, or reduced to narrators of trauma.

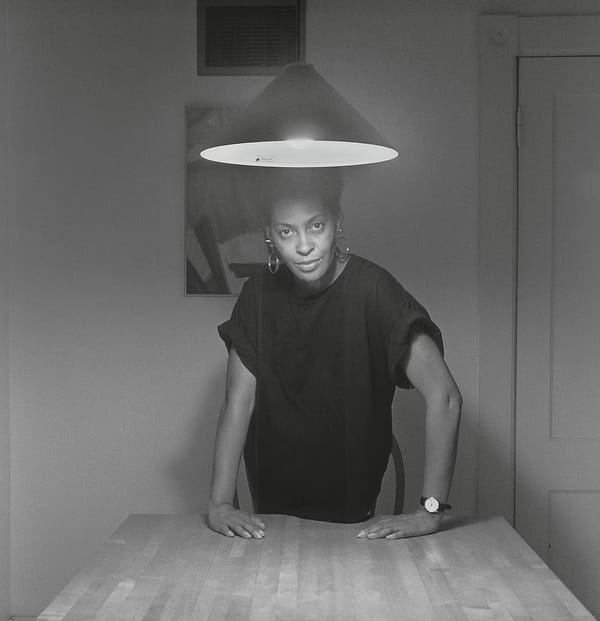

Ronan Mckenzie is a photographer and curator who explores tenderness, creativity and community in Black life. Her work often features intimate settings and soft palettes, prioritising care over spectacle. She also founded Home, a space for artists of colour to connect and exhibit.

Justin Solomon captures the quiet power of everyday Black life through warm, observational portraits. His images favour stillness, connection and presence over sensationalism. By focusing on the mundane, he affirms that Blackness is enough, unfiltered, unforced, and full.

Struggle may be part of the story. It doesn’t have to be the whole story.

Black photographers today are reclaiming the frame, not to erase history, but to expand it. They are showing us that Black life is not just something to endure, but something to live fully, feel deeply, and imagine freely.

Because the most radical image we can create isn’t one of pain, it’s one of possibility.

Share on social

If this sparked something in you, share it. Our voices are powerful, and when we lift each other up, we all see a little clearer.